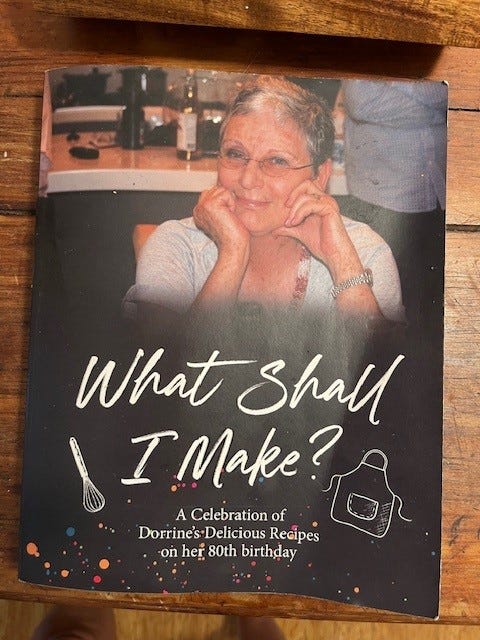

Over April, the month of Passover, I’ve been cooking my mother’s recipes, from a book I made for her 80th birthday. It’s been a nostalgia-fest, a time of ritual in the kitchen where I cook up foods that only get made once a year, (the bowels were simply not designed for ‘the bread of our afflication’ as standard fare).

Chopped liver and Danish herring, tastes acquired from childhood, are a sensory comfort in my mouth, though every bite has made me ache for my mother.

When we miss people, we can pull them near by copying what they did. So I’ve been chopping liver and Danishing the herring.

This has coincided with late afternoon heartache as I come to terms with the body-thumping truth that my father’s daily calls at 4pm have gone for good.

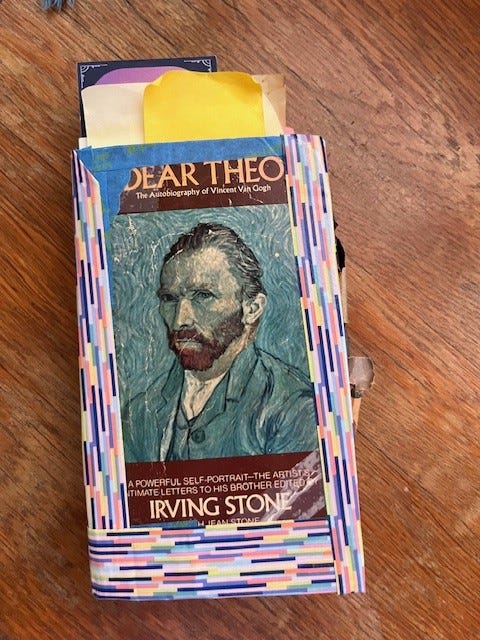

The other day I picked up his copy of Dear Theo, letters Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother. I’m reading the book as a way of standing close to my dad, peering over his shoulder, trying to understand something, I don’t quite know what.

My father adored this little book, which he kept next to his bed and read many times, evidenced by its bedraggled appearance. It was literally falling to pieces in my hands, and required a surgical job involving layers of masking tape.

He had a holy reverence for all books, as though they were sacred texts, like a Torah scroll. He would never underline, make notes in margins and highlight passages as I do. I think he thought it was a heathen act, not quite as loathsome as burning books, but close. I never managed to convince him that it was not a violation, but an adoration of texts that makes me scribble in all my favourite books.

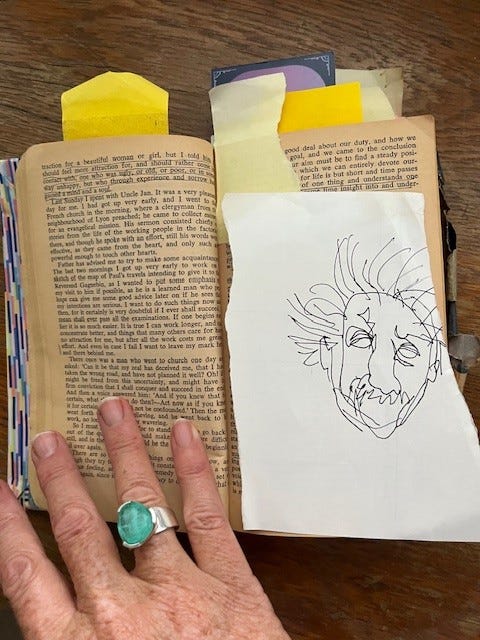

Holding this delicate copy like gossamer butterfly wings, I have tried not to interfere with the post-it notes and bits of paper he inserted in places, a kind of map of where his attention landed. But I have added myself to it, by underlining what he never could allow himself to.

It made me sad, regretful that I never paid much attention to his obsession with van Gogh, of whom he painted dozens of pictures.

But page by page, I am gathering clues, compiling questions I will never get to ask him.

I knew van Gogh’s life was dire, it’s common knowledge that he never sold a single painting in his short lifetime. But reading his diary, my understanding lands differently. Everything he undertook collapsed, nothing sturdy ever offered itself. No shred of luck ever eased his bones or softened his pillow. Even so, at night, he’d watch the way the light changed and planned the next day’s work, diligent and devoted to the shape of a miner’s silhouette or an old woman’s hands. He held onto his art, as if the life he saw around him was surely something good and precious, despite how he was forced to chew the wrongs of circumstance, day by dreadful hour. His gaze was gentle, taking in the suffering of ordinary people in their postures, the way they wore their bonnets, the shape their mouths formed.

He penned detailed letters to his younger brother, Theo, without whom I think he would have drowned in despair. This correspondence kept him tethered to brush and portrait and compassion, which offered him a lifeline to the tenuous conviction that yes, he could paint; he wasn’t mad to adhere to a sense of self the world did not mirror back to him. Theo sent him money whenever he could, and never stopped believing that what he was doing was important and valuable.

I don’t know why now, in these days, these confessions touch me so deeply. Perhaps because there comes a time in the life of anyone who has committed to a creative, hustling, unsalaried existence, where we wonder, as Vincent did, what the hell we are doing, and if there is any sane justification for our adamant devotion to our craft.

Maybe losing both parents puts one on the chopping block of mortality, and we are rendered helpless in the face of a confrontation with our own failures. When we aren’t the great successes we imagined we’d be when we were in our twenties, thirties and forties, is there still time? And more importantly, does it matter? Isn’t there perhaps a deeper point to it all?

I know I am grieving, so it’s natural for me to edge backwards, away from new technologies, and the attention-seeking strategies I learned in business courses a decade ago.

I haven’t been on social media for the past few months to rest my nervous system. I don’t want to know what’s happening in the news. My heart, far from hardening with age like a creaky artery, has softened, more easily bruised now than ever.

I remember trying to get my dad to use Facebook, and how he threw his hands in the air and declared himself unable or unwilling to participate in its performative demands. I wanted him as an old dog, to learn new tricks, to share his brilliance with more people. ‘Why?’ he’d ask. ‘I know who I am.’

Perhaps wisdom is knowing what your work is, and not being distracted by whatever we imagine these technologies will bring. For the first time ever, I get it. I have just deleted my Mailchimp account, so this Substack is my only communication with the world ‘out there’ (yes, you’re it).

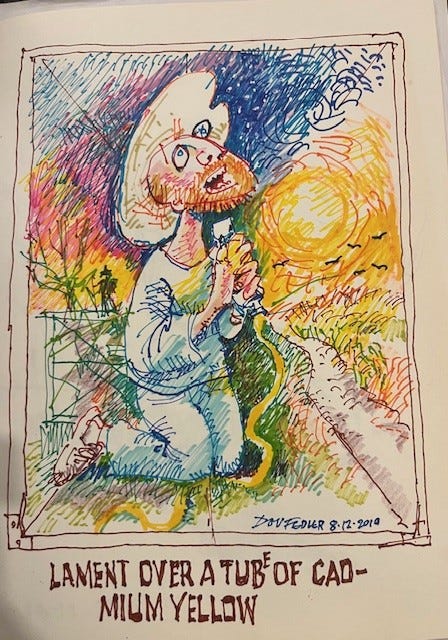

My father has left behind an enormous archive of work I have no idea what to do with. - thousands of original political cartoons, paintings, sketchbooks, and a collection of hundreds of cartoon books. I now have the task of working out what belongs where, what institution might honour his legacy, and how to return his body of work back into the world, so that whatever he made while he was here, continues to enliven and entertain.

This pulls me back into a memory of his last days when my sisters and I sat vigil at his bedside as the lights inside him were shutting down, one bodily function at a time, and weeping, one of us promised we’d take care of Nomusa, his wonderful carer, and I vowed I’d find a home for his work.

‘So many promises,’ he croaked. ‘I just want a Coke.’

Don’t take yourself so seriously, I hear him whispering. Vincent never sold a single painting. Should he have become a chimney sweep instead?

In this dog-eared wisp of a book my father held in his artist’s hands, often and with a quiet devotion, I read:

‘Well it was even in that deep misery that I felt my energy revive and that I said to myself: ‘In spite of everything, I shall rise again. I will take up my pencil which I have forsaken in my great discouragement. I will go on with my drawing….and from that moment, everything seemed transformed for me…. it was the too long and too great poverty which had discouraged me so much that I could not do anything….’

I know what I must do: keep working even harder on my craft, become a better writer and finish up the projects I have begun.

In June, I will travel to Bali to spend a week with ten writers, where I will offer whatever I know and have learned so they, in turn, can write their stories. I will try to be the ‘Theo’ to their Vincent. Perhaps at a certain time, our job is to enable others and to forget about ourselves entirely.

If the gods are willing, my plans are to run a writing retreat on Hydra in Greece in October 2026. It’s been a long-held dream of mine to create a magical week of creative engagement there, a place where Leonard Cohen spent time writing. I think it is possible to hear the voices of those who’ve inspired us when we touch what they touched and what touched them. If you’re interested in an early opt in, send me a message: joanne@joannefedler.com

My book The Whale’s Last Song is no longer available in hard-cover (a commercial decision by the publisher because hardcover is so much more expensive to produce). So if you bought that first edition, (thank you, by the way) it’s now rare. Please let me know if you ever want to get rid of your copy, I’ll gladly take it.

It’s coming up for Mothers’ Day, and if you’d be willing to purchase a copy or two of the much cheaper softcover here as a gift for yourself, or someone who is a mother, that would be a big gift to me.

It would also make a huge difference to my standing with my publisher if we sold a few more hundred copies or so. If you enjoyed the book, and have moment, a review on Amazon or Goodreads would also boost the various algo-whatevers… who knows if it makes a difference? Not me. But they say so.

Without some ‘commercial viability’, in which the pourings of my soul make money for publishers, I am unsure if my memoir about losing my mother will find a traditional publishing home. But never mind - I will share some chapters here in the coming months, because …. WWVD? (What Would Vincent Do?)

Thanks for reading me.

With love, always